End of Life Care Nursing

End of life care nursing takes place across a spectrum of settings. In this post, I look at the different places where it is delivered, and the associated challenges. I also recall the types of questions that friends and family of patients asked me.

Acute Settings

Acute Settings

Palliative and end of life care nursing in acute care can be difficult, for a number of reasons:

- Staff shortages

- Limited training and education in end of life care among staff

- Limited choice of food for the patient, when dietary intake is already reduced

- Outbreaks of infections on wards, delaying fast track discharges

- Delayed discharges due to unavailable service provision in the community

Hospice

Because hospices specialise in end of life and palliative care, they provide some key benefits in comparison to acute care:

- Staffing ratios are usually better

- The staff are educated and trained to deliver palliative and end of life care, benefitting the patient and their loved ones

- Better choice of food and drinks

- Access to a wider range of services

- More options for personalised care

- Less noise and more private rooms available

Unfortunately, there is often a stigma associated with the concept of hospice care. People think they will only be admitted to a hospice when they are dying. But the truth is hospice care can be extremely beneficial to patients receiving palliative care, who aren’t close to the end of their life. In fact, the World Health Organization recommends early access to palliative care and services, with one of the benefits being reduced hospital admissions.1

Hospices have strict referral criteria, and often have waiting lists for admissions. Normally, there are no long term stay options, although there are exceptions. The maximum length of stay is usually around 14 days. Patients receiving end of life care are usually admitted for symptom management in the last days or hours of their life.

The majority of hospices receive funding through a combination of charitable donations and the NHS. In addition, some hospice consultants work across acute and hospice settings, which helps with continuity of care and faster access to services.

Community

Care packages in the community usually include visits of up to four times a day. District nurse visits are often once a week, unless the patient’s symptoms worsen or they start using a syringe driver, which needs daily replenishment.

The patient may have access to a hospice to home service, or to a Palliative Care Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS). Unfortunately, this varies a lot from postcode to postcode. And equipment availability is also often location dependent.

Hospice Palliative Care CNS’ usually work alongside district nursing teams.

Nursing Homes

Some nursing homes now have several beds specifically set aside for palliative care. Community matrons or care home matrons often manage these. They deliver the patients’ care with support from a hospice and other professionals, in a multi-disciplinary team approach.

Fast Track Discharge

Fast track discharge from hospital can be arranged if clinicians believe the patient is in the last 12 weeks of life. Funding is via clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and integrated care boards (ICBs). Palliative Care CNS’, who are the link between acute and community settings, often complete the fast track paperwork.

Patients are discharged to their own home or a care home with:

- A care package (own home)

- Equipment

- Medications

- All required referrals (for example district nurse, hospice)

In addition, more funding is often available for measures which will improve the patient’s quality of life. CCGs and ICBs provide this funding, which is often granted when applied for.

Questions I was Asked

Some of the types of questions that patients’ loved ones asked me when I was delivering end of life care included:

‘She’s comfortable now and hasn’t been settled all night. Do you really need to reposition her?’

‘Do you have to disturb him? We’ve just changed over and I haven’t spent any time with him.’

‘Is there nothing else you can do for that awful sound, is he uncomfortable?’

‘Can you please turn him onto his right hand side to face Mecca?’

‘The carers came at 9pm last night, do you think she will be okay? Because she has been in that same position for 11 hours.’

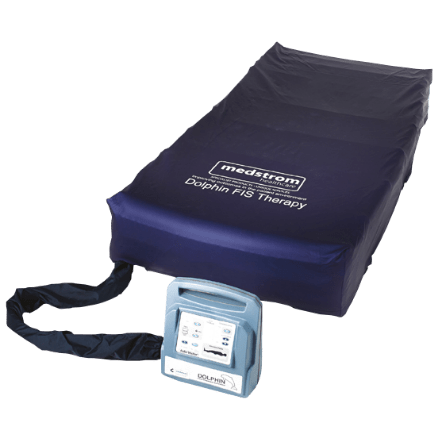

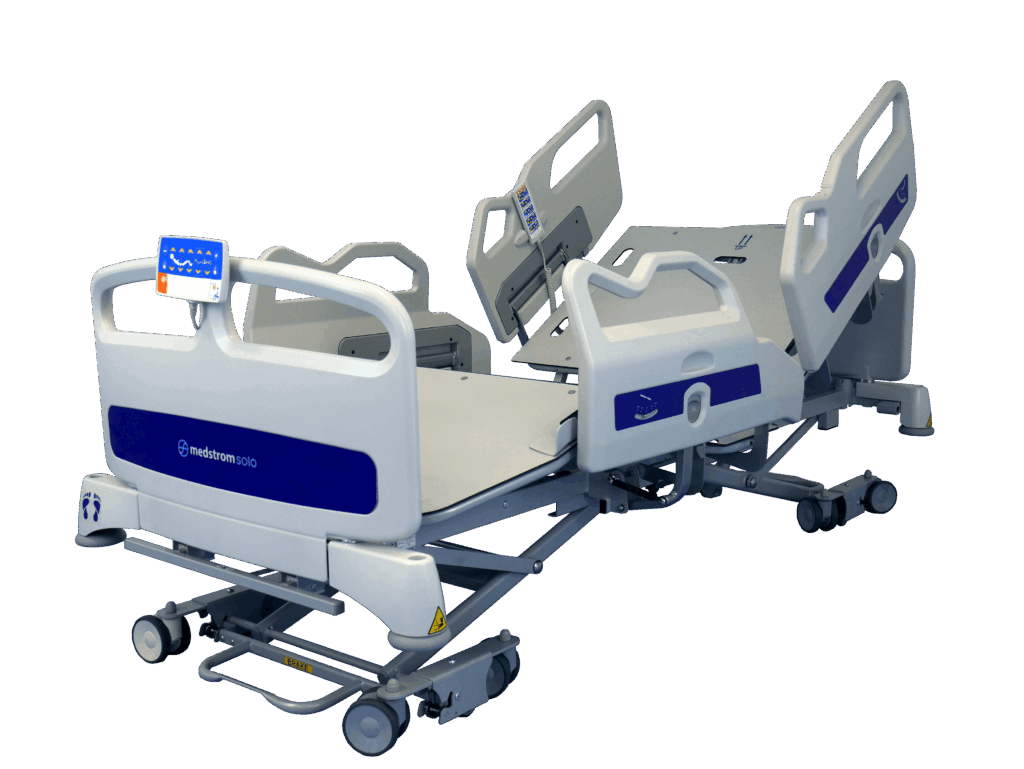

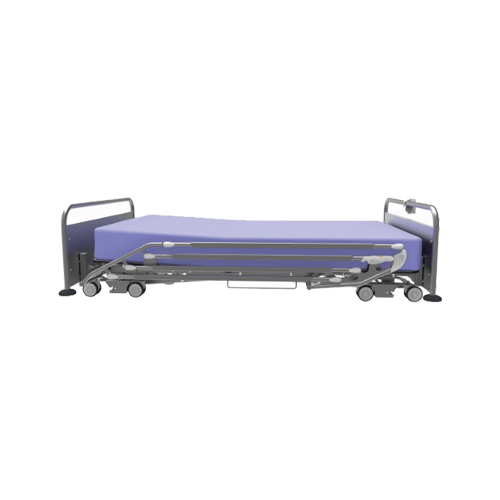

Equipment such as an electric profiling bed or a mattress which helps to reduce turning frequency whilst still protecting skin can help to lessen some of these concerns. In what is a very stressful time for loved ones, any innovations besides medication which can help to make the patient more comfortable are, in my experience, very welcomed.

References

-

Palliative care (2020). World Health Organization. Available here.